Debunking Myths About Migration

Hein de Haas visited Duke for a riveting talk about what is missing from current conversations about migration.

By Emily Klein MSGH'24

Hein de Haas, a professor of sociology at the University of Amsterdam and co-director of the International Migration Institute (IMI), delivered an eye-opening talk on his newest book, "How Migration Really Works: The Facts About the Most Divisive Issue in Politics," on Feb. 8 in an event co-hosted by the Duke Center for International Development and Duke Office of Global Affairs.

In the book, de Haas debunks 22 myths about migration that he argues prevent leaders from achieving comprehensive migration reform in countries worldwide. He dove into several of those myths during his talk, explaining how the current dialogue around migration lacks nuance.

Myth: We live in times of unprecedented mass migration.

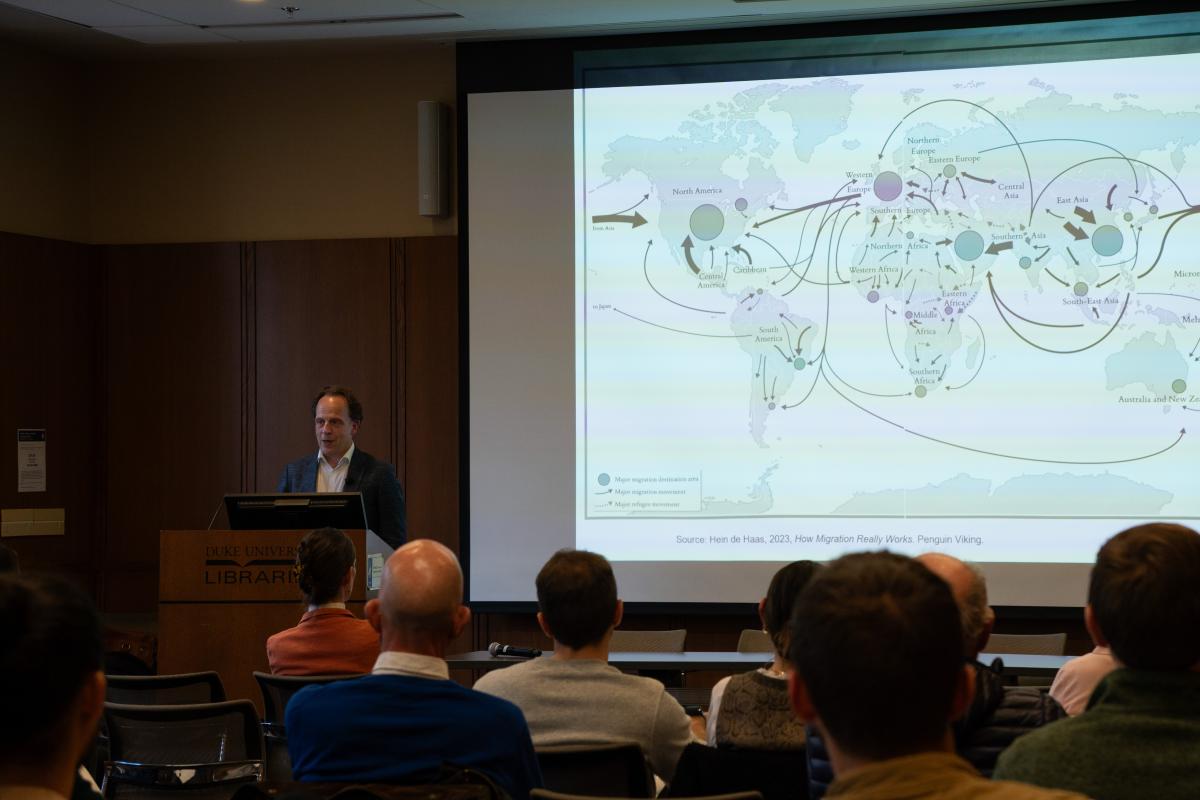

de Haas shared several graphs with the audience showing that although migration has increased in recent years, migrants make up around three percent of the worldwide population, a percentage that has remained steady since 1960. News outlets and journalists tend to exaggerate the problem, creating a false narrative that there are more migrants than ever before. Even government agencies might overstate the issue to attract more funding. de Haas argued that most migration occurs within countries or between neighboring countries, so the images we often see of a mass exodus into Europe are misleading.

Myth: Border restrictions reduce migration.

Most migration channels involve a complex movement of people back and forth between countries. “If you really want to understand migration from a sociological perspective, you’d have to understand that migration is a process of coming and going,” de Haas said. Understanding this reveals how restrictions can actually lead to more migration when they disrupt these circular channels. They prevent people from going back and forth, pushing migrants to settle permanently in the country that’s implementing restrictions.

de Haas also explained “anticipatory surges,” where migrants will work to enter a country faster when they know a restriction is going into effect. de Haas detailed a striking example of this when Suriname achieved independence from the Netherlands. To limit the flow of Surinamese citizens into the Netherlands, Dutch politicians advocated for Surinamese independence, which would take away Dutch citizenship from the Surinamese population. The two countries reached an agreement that until 1980, the Surinamese could go to the Netherlands and get a Dutch passport. In those 10 years before independence was finalized, 40% of the Surinamese population moved to the Netherlands and 50% still live there today. While the policy move was an effort to decrease the number of Surinamese citizens living in the Netherlands, it had the opposite effect.

Myth: Development will reduce migration.

Another common myth is that people are more likely to leave less developed countries to seek opportunities elsewhere. de Haas pointed out that although many low-income countries are in Africa, it is the least migratory continent in the world and most migrants stay in the region where they’re from. He explained that migration occurs when someone has both the capability and aspiration to migrate. Someone in a low-income country might have the aspiration but lack the capability. In high-income countries, residents often have the capability but lack the aspiration. That’s why middle-income countries are the main drivers of migration, debunking the myth that investing in the development of low-income countries would decrease migration.

Fact: Labor demand is the biggest driver of migration.

de Haas ended his talk by explaining that while politicians might say that violence, misery, poverty, invasion, or climate change drive migration, they never mention that the main reason people migrate is because there is a demand for their labor. “It’s an anti-immigration myth that migrants take away jobs and drive down wages,” he said. The reality is that there is a structural labor shortage in many high-income countries that migrants fill, which is especially true when the economy is doing well.

When describing the current dialogue about migration, de Haas pointed out that “politicians that talk extremely tough about securing the border actually don’t do anything to prevent undocumented migrants from working.” He drove this point home with a shocking statistic that only 10 to 15 companies in the U.S. are prosecuted for employing undocumented migrants each year.

de Haas argued that we need a new way of thinking about migration that captures the nuances of why and how people migrate. He concluded his talk by sharing his hope that there will be “a future generation of politicians that has the courage to tell a real story about migration.”